In Part One we researched different types of garments that

were worn for different occasions. In

the course of a day, outfits would be changed many times. This was not an easy task as many garments,

undergarments, corset, crinoline, etc were involved. As you can imagine, this would likely require

help. For women of the era, and

re-enactors alike, the foundation of a successful period garment is the proper

set of undergarments. In Part Two, let’s

see how a 19th Century lady would’ve gotten her game on.

The first thing over

the head is the chemise. It is pronounced

shea-muuz. A chemise is like an

undershirt made out of cotton or linen and its purpose is to provide a layer

between the skin and the corset and to protect the corset from getting dirty

(oil and grime from the skin). It was easier

to launder the chemise than the corset.

The chemise was also much less expensive to replace. Sometime around the early 1900s, the chemise

and drawers were combined into one under-garment. This was welcome, as it provided modesty and

garment protection with fewer layers.

Next, came the

drawers (a.k.a. pantaloons) also made of cotton or linen, tying at the drawstring

waist (typically with ribbon). There

were two ways a gal could go: closed

crotch or open croch. Given all the

layers worn, open crotch drawers were more practical and more common until the

1900s (imagine using the powder room while sporting all those skirts and paraphernalia). Open crotch drawers were just as they sound…so

we’ll be skipping the x-rated image and show, instead, the closed crotch

version.

Note to 19th

Century Self: You may want to put your

drawers on, then your shoes and stockings (held up with garters) and lastly,

your corset. If you’ve ever had the

pleasure of being bound up in a corset, you know how hard it is to bend over

once cinched up. Back in the day, a lady

would’ve had help dressing. If you don’t,

put your shoes and stockings on first!

Now, for the dreaded

corset which would’ve squeezed your body into a shapely, fashionable form, with

steel bars down the front and whalebone on the sides—breathing optional. A 19th Century corset had a busk

in the front to close the corset and add shapeliness. A busk is two metal strips with hooks (nails)

and eyes that closed the corset in the front.

The corset laced up the back, but could be unhooked in the front without

a complete unlacing necessary in case of emergency. “Oh, no! Help!! My skirts are on fire!” or “Oh,

no! I think I’ve eaten something foul!!”

Corsets were the rage. Nineteenth-century advertisements for corsets sang their praises, while doctors warned of various health risks for corset wearers including displacement of internal organs, improper function of the lungs, internal organ deformity, etc. Despite the risks, the rigid bodices were a common clothing item for centuries.

Remember the scene from Gone With The Wind when Scarlett is

clutching the bedpost and Mammy cinches down her corset to achieve the

desirable (and highly restrictive) tiny waist?

I believe 18” was the watermark.

Scarlett complained, as certainly did women of the time, but

to what avail? They were doomed to their

position in society, slaves to fashion, corseted and cosseted, and striving to

be pleasing to a man’s eye—no matter the cost.

Women really did suffer for the sake of fashion with ridiculously large

crinolines and heavily boned, tightly cinched corsets—all greatly restricting

their movement and bringing discomfort.

Over the corset would go a corset cover which was a short shirt-like garment a lady would put on to protect her expensive outer garments from rubbing against the nails (hooks) of the busk and tearing the clothing.

Over the corset would go a corset cover which was a short shirt-like garment a lady would put on to protect her expensive outer garments from rubbing against the nails (hooks) of the busk and tearing the clothing.

A decency skirt was a slip like undergarment worn over the

drawers. It was worn to protect the

nether region from view if the skirt was blown up by wind, if the woman was

blown over by wind (really happened!), a fall or some other calamity that would

expose an open crotch in all its glory.

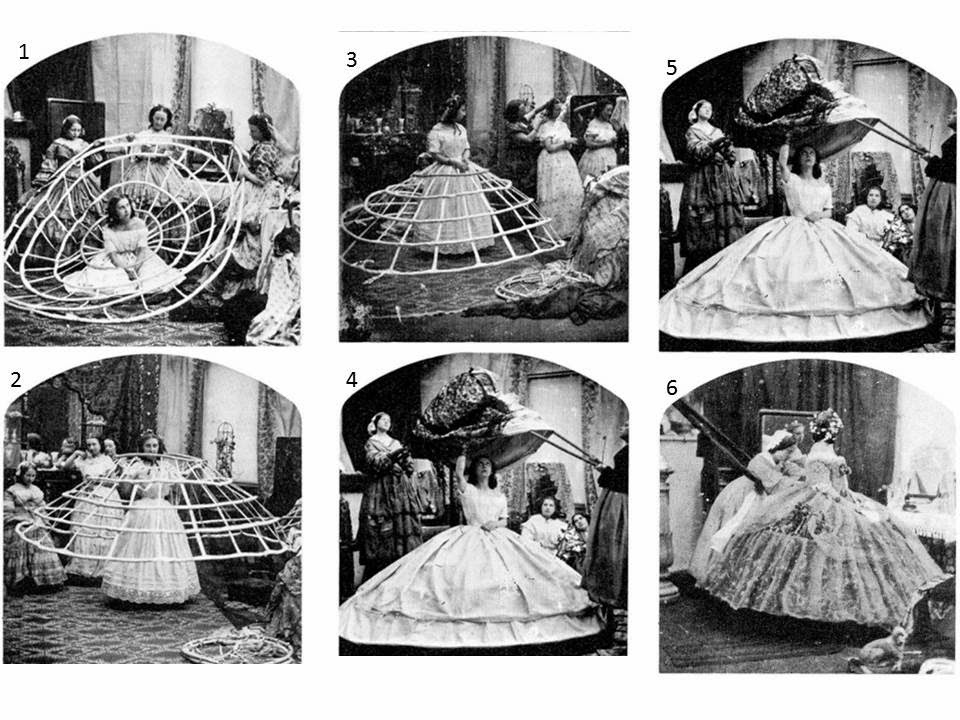

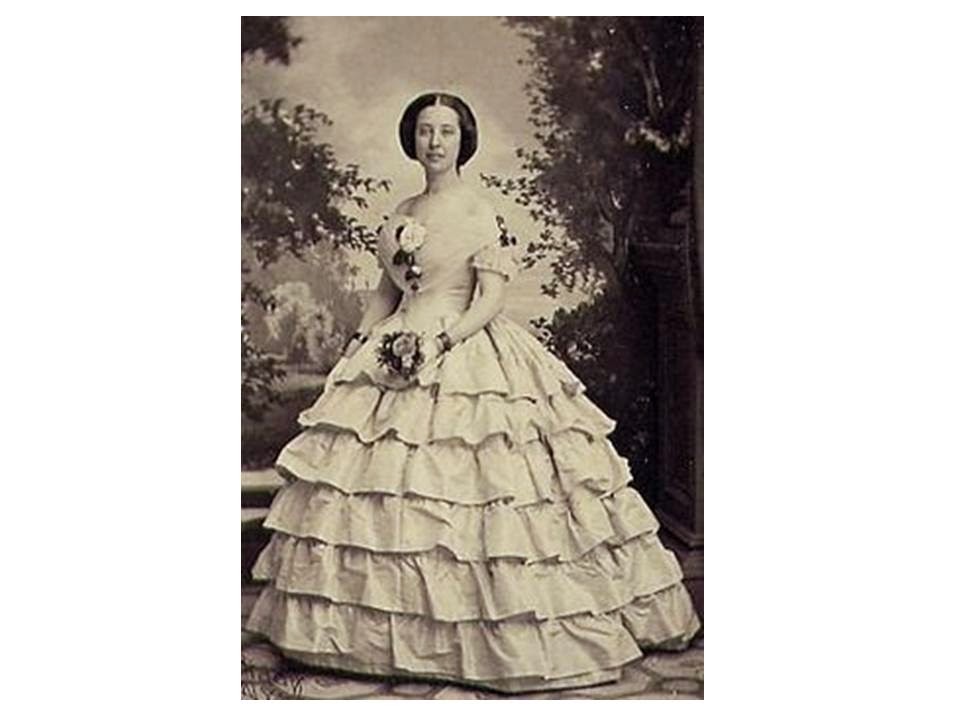

The last undergarment put on before the dress was the crinoline, also known as the hoop skirt. Popular women’s fashions in the mid-1800s required full crinoline underskirts. As fashion trended toward fuller skirts, women were burdened with having to wear several layers of stiff, heavy, and uncomfortable, fabric underskirts to get the effect. Then…petticoats were replaced by hoop crinolines which, even though they had a metal cage, were lighter by far than layer upon layer of petticoats. There was less weight and crinolines allowed skirts to expand even further.

Early crinolines were made from horsehair (the French word for horsehair was crin) and wool—which could both be itch and scratchy. Smaller hoops were worn for everyday day dress and the got larger as they even got more formal, with the most hoops reserved for balls and weddings. Some crinolines measured more than four yards around at the base (hemline)!! Women wearing these skirts had to move carefully to avoid knocking things off of tables or backing into the fireplace, as they seemingly floated around a room. How many women in crinolines do you think could fit in a room???

The last undergarment put on before the dress was the crinoline, also known as the hoop skirt. Popular women’s fashions in the mid-1800s required full crinoline underskirts. As fashion trended toward fuller skirts, women were burdened with having to wear several layers of stiff, heavy, and uncomfortable, fabric underskirts to get the effect. Then…petticoats were replaced by hoop crinolines which, even though they had a metal cage, were lighter by far than layer upon layer of petticoats. There was less weight and crinolines allowed skirts to expand even further.

Early crinolines were made from horsehair (the French word for horsehair was crin) and wool—which could both be itch and scratchy. Smaller hoops were worn for everyday day dress and the got larger as they even got more formal, with the most hoops reserved for balls and weddings. Some crinolines measured more than four yards around at the base (hemline)!! Women wearing these skirts had to move carefully to avoid knocking things off of tables or backing into the fireplace, as they seemingly floated around a room. How many women in crinolines do you think could fit in a room???

Although the hoops were much lighter weight than the wool and horsehair, they had one problem: a women had to learn how to sit properly in them or they would swing up exposing her (likely) crotchless drawers! In a day when modesty forbade seeing an ankle, there would've been vapors (fainting) and social scandal if a woman’s nether regions were exposed. Crinolines made it impossible for a woman to sit down in a carriage. While traveling she often had to kneel or sit on the carriage floor. Ahhh, the price of fashion.

There wasn’t such thing as dresses with upper and lower

parts sewn together until the turn of the century. Until then, the bodice (taille) and skirt

(sometimes with a train), as separate pieces, made the dress.

A taille (bodice) fit the body very tightly, sometimes looking

like a jacket and sometimes like a blouse. Low

décolletés with short or no sleeves were worn on evening gowns or ball

gowns. The taille was tight fitting and

its lining was stiffened with whalebone (in addition to the whalebone and steel

stiffening the corset). Along the bottom

of the taille might be garniture, which was decorative pieces of trim (lace,

fabric, cord, ruffles, ribbons or bows).

The garniture would be cleverly arranged to give the appearance that the

garment was all one piece. Garniture was

an important part of the ensemble.

After ALL the undergarments and crinoline were on, the taille and skirt would be put on. A woman could not have done this by herself and would've had help in dressing.

Time to accessorize!! On with hat and gloves (always), grab an umbrella (for rain or sun), a fan, maybe a walking stick--and that was one outfit down for the day!! Fully dressed, it was common for a woman’s clothing to weigh 40 pounds. That’s like strapping a 40 pound bag of dog food to your back and carrying it around all day!!

Time to accessorize!! On with hat and gloves (always), grab an umbrella (for rain or sun), a fan, maybe a walking stick--and that was one outfit down for the day!! Fully dressed, it was common for a woman’s clothing to weigh 40 pounds. That’s like strapping a 40 pound bag of dog food to your back and carrying it around all day!!